The Alberta Drug Model is a Christian institution: Part 2

The drug supply is shifting so rapidly, how could old-school detox and treatment methods possibly keep up?

In Part 1, I described the degree to which Alberta substance use care is dominated by Christianity and abstinence-only approaches. I focused on long-term, transitional facilities — the end point of the UCP’s recovery-oriented system of care.

Here in Part 2: how the drug supply is shifting in ways that current ‘detox' models and the faith-based and 12-Step programs that follow are hopeless to address.

Opioids & overdose deaths in Alberta

People who have been using drugs for a while will be quick to tell you they miss the old days of heroin: it wasn’t always good quality, but it rarely resulted in overdoses.

Most people mark 2014 as the year fentanyl showed up in Alberta. Dr. Esther Tailfeathers of Kainai Nation recalls realizing quickly how the sudden spike in overdoses she was seeing in Standoff that year were opioids: when they caught them in time, they were able to reverse them with naloxone. In Kainai, a Nation of around 10,000, parents have since buried hundreds of their children.

Around 50 times more potent than diacetylmorphine (heroin), fentanyl quickly replaced heroin and other opioids in the supply — its potency makes it that much easier to conceal and distribute.

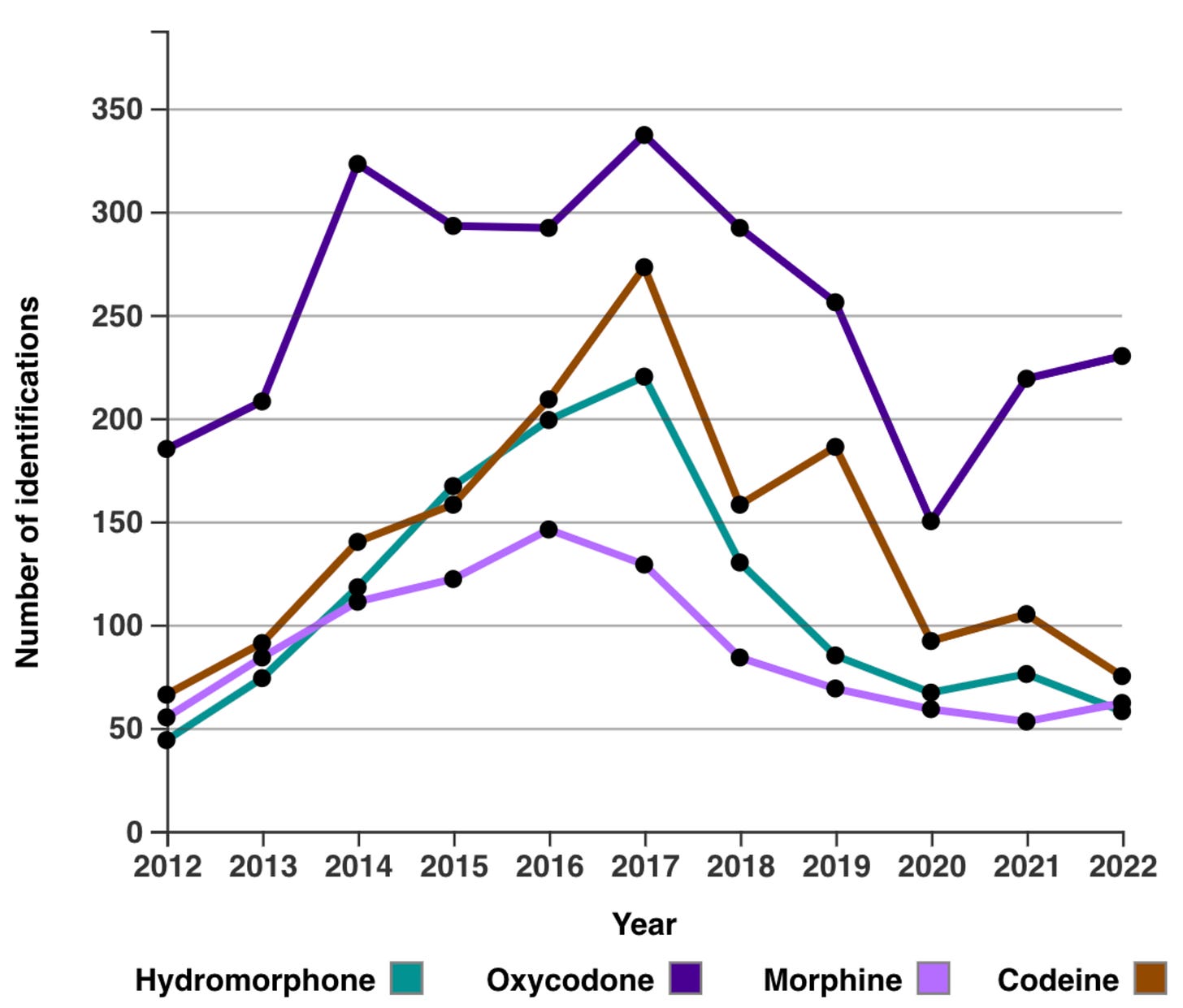

Here, you can see how pharmaceutical opioids like oxycodone (Oxycontin), hydromorphone (Dilaudid), codeine (Tylenol-3) and morphine all fell off in frequency starting in 2016-17.

Incidentally, prescribing of pharmaceutical opioids in Alberta decreased by 30% between 2016 and 2021. You can see how non-pharmaceutical opioid overdose deaths have exploded over this period, which also coincided with the increasing dominance of fentanyl among police-seized samples.

This graph, from a slideshow that former Chief Medical Officer of Health Dr. Deena Hinshaw presented to the United Conservative Party’s 2022 Safe Supply committee, shows how pharmaceutical opioid deaths (green) increased from about 85 to 192 over a period of relative stability in prescribing rates. Starting in 2017, de-prescribing coincided with an explosion in non-pharmaceutical overdose deaths which were already rising alongside fentanyl.

Benzos and informed consent

But fentanyl wasn’t the end of the story. Since 2016, benzodiazepines have been a factor in 3 to 14% of opioid-related fatalities in Alberta.

Benzos are a class of drug known for challenging withdrawal symptoms: like alcohol, withdrawal can result in seizures, brain damage and fatality. Most of us can only imagine the physical difficulty of withdrawing from multiple substances at once. What we’re seeing now is an entire population of people being repeatedly subjected to withdrawal from ‘benzodope’ (combination of benzodiazepines and opioids).

The first, second and third quarter in 2021 each saw 37-58% increases in the presence of benzodiazepines among police-seized drugs. This volatility has since stabilized — likely a reflection of more consistent drug trade and a contributor to the decrease in deaths — but how are people who use drugs supposed to keep up? If anything like this occurred in alcohol or any regulated drug there would be riots.

While some people seek out the comforting “warm blanket” of benzodope, the volatility in potency leaves many folks extremely vulnerable during overdoses that can last many hours. Crackdown host Garth Mullins also recently told me how activism and community organizing is hindered by the way that benzodope results in memory lapses among otherwise sharp, motivated individuals. Maybe it’s not an accident.

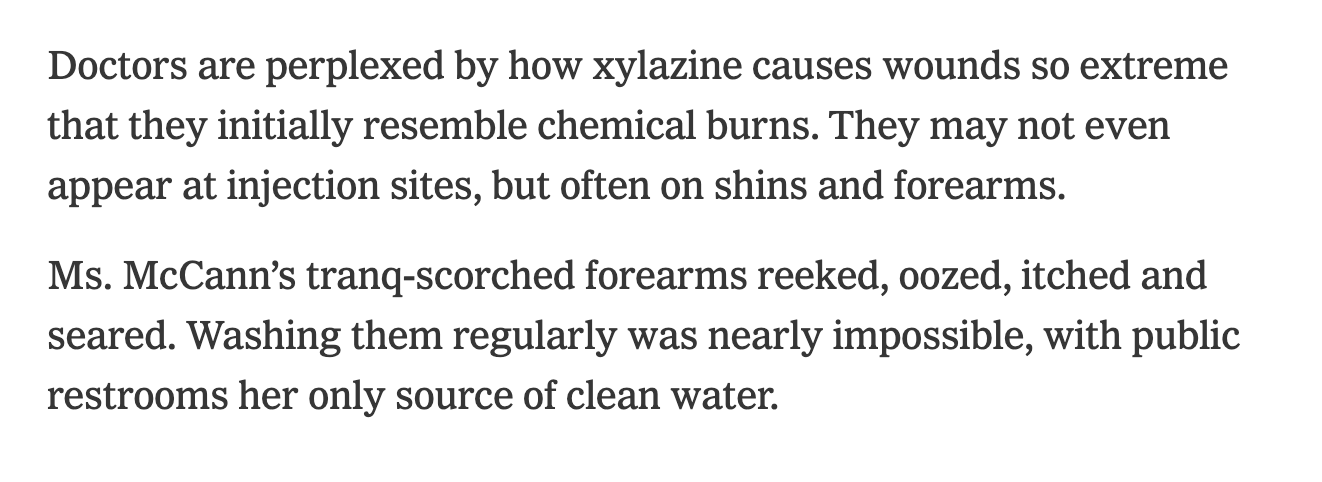

The bottom line is that at a population level, nobody is consenting to the changes in the drug supply year after deadly year. We’re only now beginning to see the onslaught of xylazine, or ‘tranqdope’ alongside all this: you need only look at Philadelphia and Puerto Rico to know what comes next.

Is Alberta making space for shifting supply?

One look at the Alberta Health Services summary of the available detox options shows how woefully unprepared we remain in helping people come off fentanyl and benzodope — let alone xylazine. Two of the 16 facilities, both in northern Alberta, don’t offer medical withdrawal at all: just strap in and hope for the best.

With almost half of detox spaces placing smoking restrictions on their clients, it’s no surprise that at least 31% of detox spaces in facilities that provide such details indicate restrictions on permitted medications — and remember, these are prescribed only. Restrictions on basic opioid agonist treatments such as methadone, buprenorphine-naloxone (Suboxone) or morphine (Kadian) are found in around 40% of detox spaces.

This is not what it looks like to meet people where they are.

At the heart of all of this is a question: is more medical withdrawal or detox capacity even what's missing in an era of extreme relapse danger, when opioid maintenance is more medically accepted, and when drug use is not the root of many people's struggles against inequity?

What is ‘missing’ depends on the system's stated and unstated goals. Combined with our discussion on the Christian abstinence focus of longer-term transitional care in Part 1, the goals come into sharper focus when we examine the Intensive Adult Substance Use Treatment Facilities — the next phase after detox.

Look for that in The Alberta Drug Model is a Christian institution: Part 3.