We can forecast drug poisoning deaths without provincial data

Spin, minimization and delayed data are the orders of the day in Alberta drug policy. How can we cut through the manufactured noise and tell people the truth?

The original form of this post showed exaggerated data, which have been updated with validation from newspaper announcements during the periods of interest. Given that 3,362 people died of “unknown cause” in 2021 — the top ‘cause of death’ in Alberta — we can expect a similar medical examiner backlog for 2022 that will continue to drive these drug poisoning statistics higher.

Spin tactics for election year

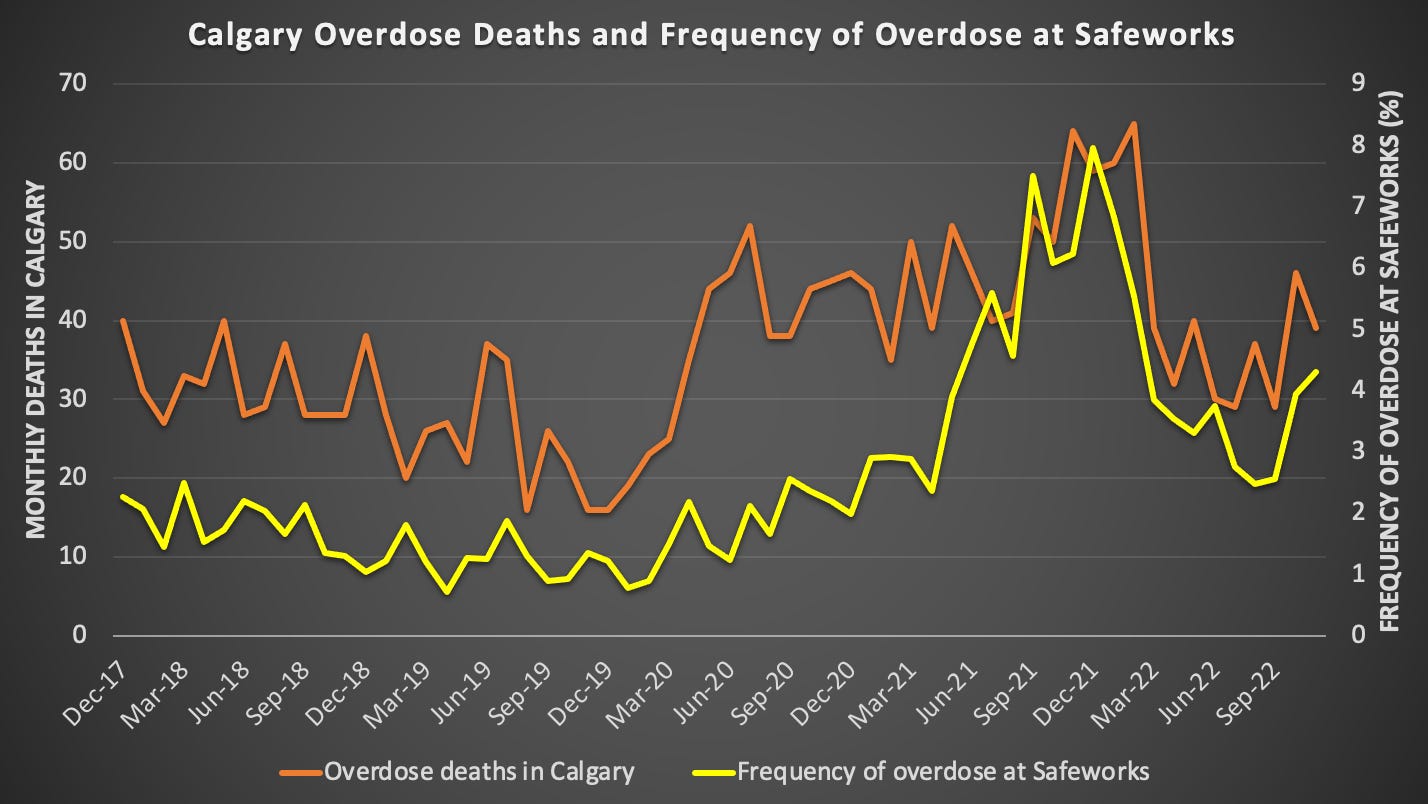

Safeworks, Calgary’s only supervised consumption site, has released a report every month since it opened in 2017 detailing how many people visited, used drugs, and experienced an overdose. You can find the reports here.

Every month, we wait for the province to release the mortality count. They’re always late, often by 3-4 months, and announcements since April have been made with tremendous fanfare, appearing to show downtrends in mortality (despite still showing death counts far above pre-pandemic levels). You can find those data here.

But the announcements are not just late. Turns out, they’re also false.

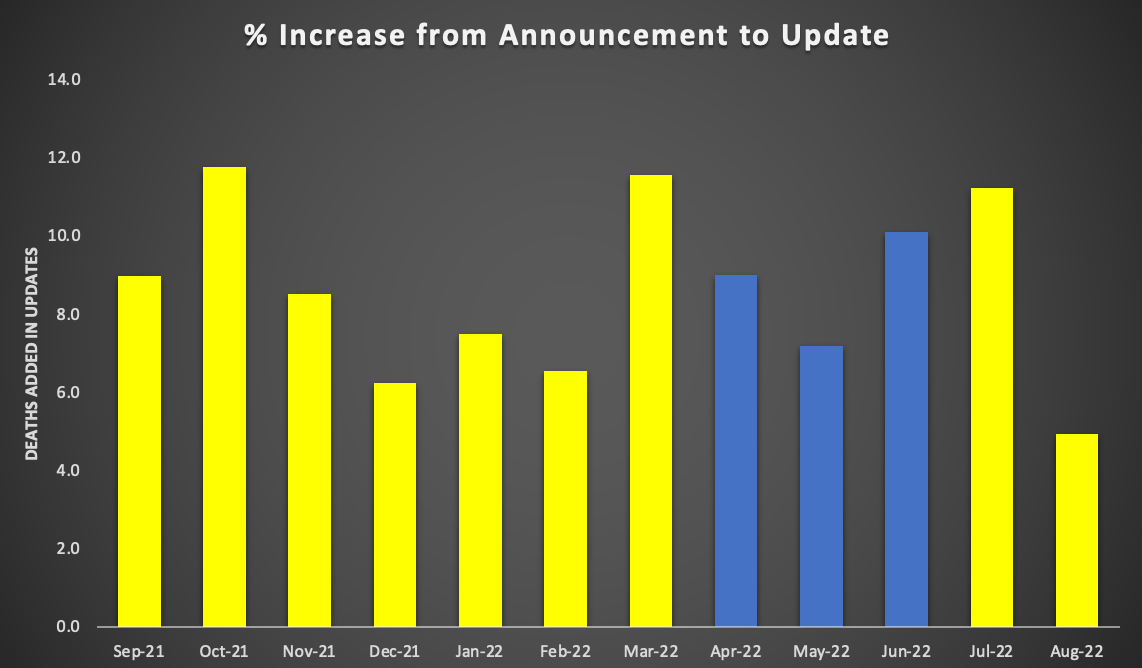

When we look back at the media reports published between September 2021 and August 2022 (I was unable to find media reports for April, May and June 2022, so used my spreadsheet logs from that period), the average increase in mortality each month between announcement and updates is 9%.

That means Alberta hasn’t had any months below 100 drug poisoning mortalities since the pandemic hit — whether you only count opioid-specific mortalities or all substances together.

The important thing is, when the Alberta government announces its drug toxicity data, we must apply a correction factor of at least 9% (probably much higher) to the mortality count. So the newly announced September to November data should be adjusted: 116 up to 126 dead for September, 127 up to 138 dead for October, and 123 up to 134 dead for November.

Media would be justified in applying a 9% upward correction factor to any monthly government announcements on drug poisoning mortalities.

Taylor Braat of CityNews Calgary managed to tease this admission out of Minister of Mental Health & Addictions Nicholas Milliken:

When BC announces its counts, they include all situations that were likely drug poisonings. In Alberta, our medical examiner process takes longer: a friend DM’d me today to say their dad died of a drug poisoning on Christmas, but the examiner said it’d be 8 months til they get results. Eight. Months.

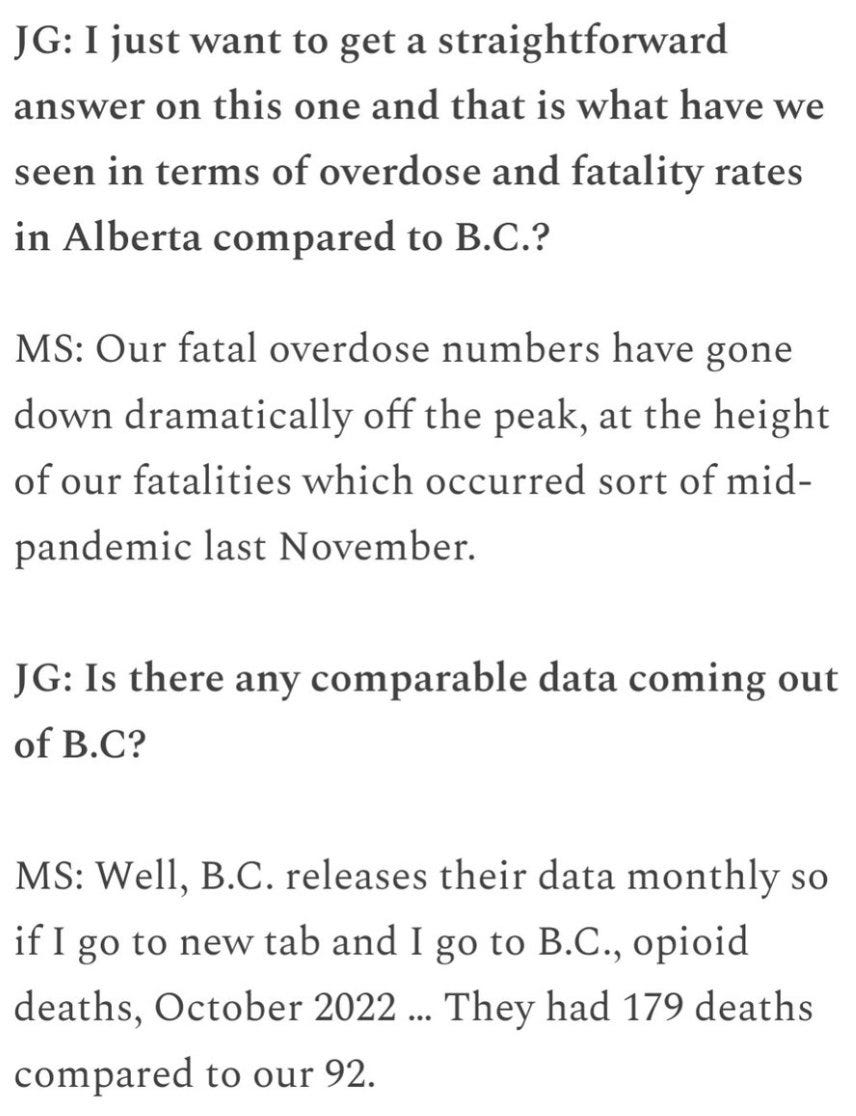

But when Premier Smith’s Chief of Staff Marshall Smith, architect of the Alberta Model with lots on the line here, told us in his recent ‘interview’ with Jen Gerson that Alberta and BC have diverged so much that BC was now doubling Alberta in deaths, he was leaving out some key information:

First, the number that he pulled, 92, does not exist and never did. The number announced on Friday is 127 Albertans dead from drug toxicity in October, of which 121 were opioid poisonings, far more than 92. Second, we now see we must apply a correction factor to the reported number to account for the people that medical examiners will later reveal to have died from drug toxicity.

The final tally for Albertans dead from drug toxicity in October will likely wind up near 138. Accounting for population, that is only 10% lower than BC’s October count of 179 — similar to trends going back years.

The fact is, Alberta seems to lag BC by about a year in the crisis. This is a complex issue and likely results primarily from differences between the drug supplies and people’s adaptation to changes in them.

A proxy for missing data

Coming back to the reporting at Calgary Safeworks, I used this to develop a predictor for the death count that might help forecast in the absence of reliable provincial reporting: the frequency of people overdosing at the supervised consumption site.

In late August, 2022, I compared these data in a twitter thread. Key finding:

The drug poisoning death count is tightly linked to how frequently people overdose at Safeworks, which approximates drug supply toxicity and volatility.

These data were harnessed by CTV Edmonton’s Kyra Markov for a beautifully rendered piece dismantling the Alberta government’s claim that government policy is responsible for reduced deaths since the latest peak in December 2021.

Look how closely the data track from the start of record-keeping in December 2017. Yellow shows how often people overdose at Safeworks. This hit a peak in December 2021: 8 of every 100 site visits resulted in a non-fatal overdose. In orange, Calgary’s monthly mortality count hit a peak in February 2022.

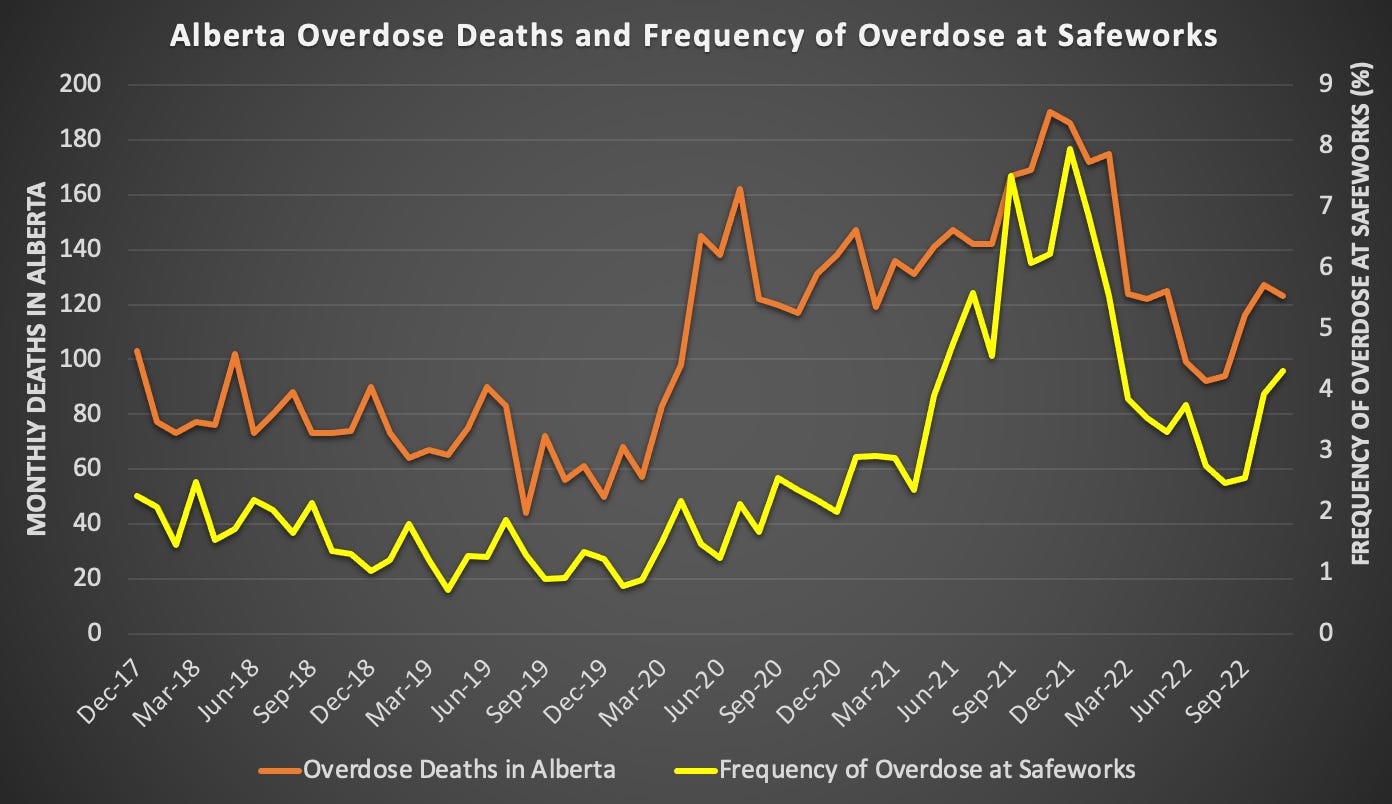

Repeat the same analysis swapping Calgary mortality out for all of Alberta yields a similar result. This indicates that the drug supply accessed by Safeworks’ >3,000 monthly visitors is reflected across the province.

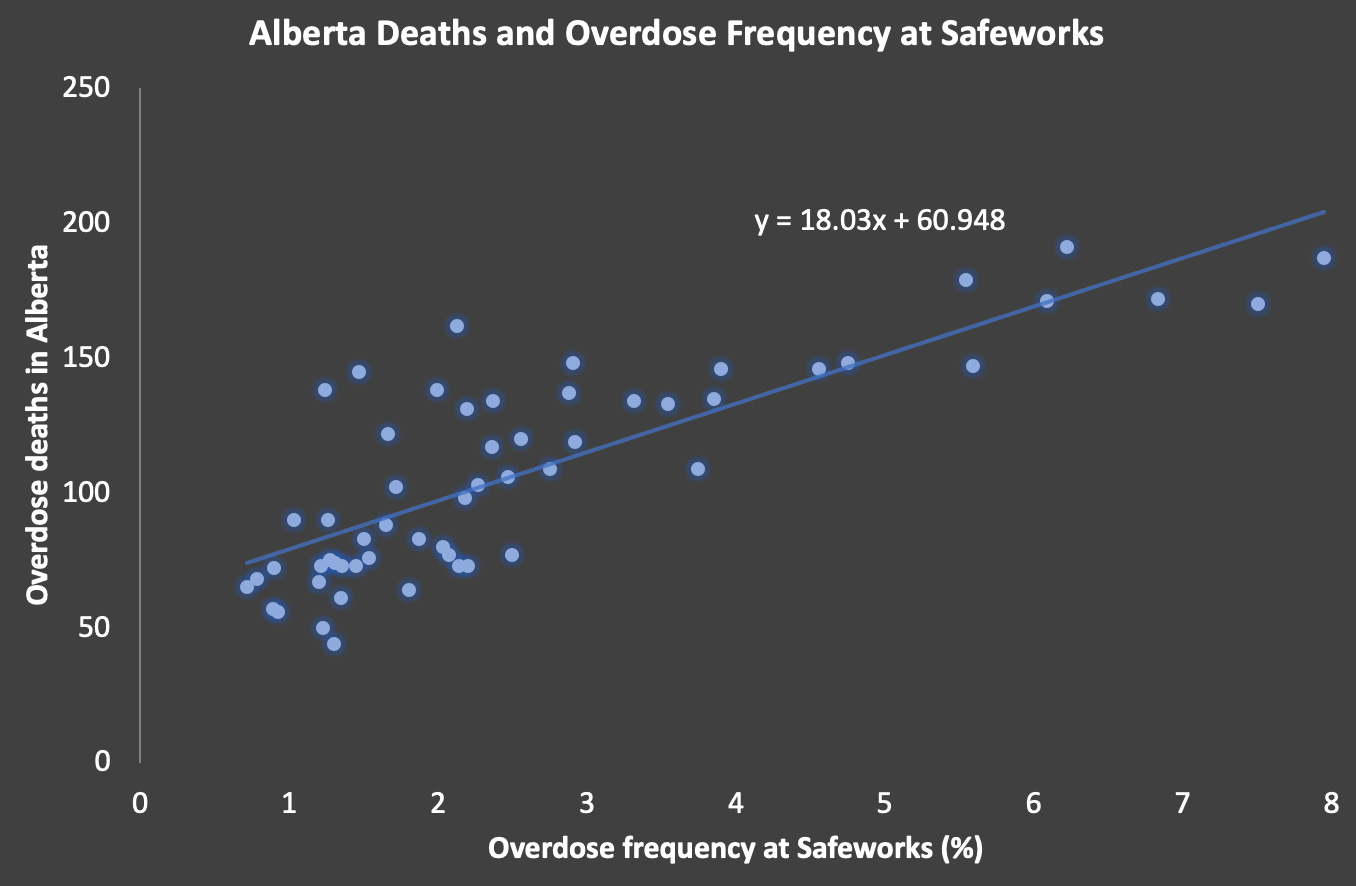

We can calculate the relationship between overdose frequency at Safeworks and mortality by plotting them directly against one another. Look how closely they align. This relationship is highly robust (Spearman correlation r = 0.72, p<0.0001).

Forecasting in the absence of data

So using this derived equation, we can plug in the Safeworks-reported overdose frequency of 5.88% and determine an eventual tally for December overdose mortality:

There could be over 160 deaths counted by the time the dust settles — the highest since February 2022.

I am sorry to everyone whose loved ones were killed by drug prohibition in December 2022 and every month that preceded it. Without meaningful effort to regulate the supply, I’m afraid the worst is yet to come.

Edmonton: want to work together to reverse this emergency? I’ll be there for an event you should come out for, hosted by Councillor Michael Janz and some great organizations, on February 16 at Metro Cinema. RSVP here.

The data visualization of overdose deaths vs Safeworks overdose is staggering. Thank you for sharing, Euan.